When Mollie and I headed southward through the suburbs of Paris with Hetty Second, our 1947 500 c.c. Matchless, we had a fair idea that we had committed ourselves to an arduous journey But we were unaware just how arduous it would be, or that a mean depression in Iceland was already plotting to supply us with something exceptional in the way of weather, which washed away our dreams of basking in the sun on the Dalmatian Coast.

When Mollie and I headed southward through the suburbs of Paris with Hetty Second, our 1947 500 c.c. Matchless, we had a fair idea that we had committed ourselves to an arduous journey But we were unaware just how arduous it would be, or that a mean depression in Iceland was already plotting to supply us with something exceptional in the way of weather, which washed away our dreams of basking in the sun on the Dalmatian Coast.

Yet, if as a holiday it was a wash-out, it was eventful, and so crammed with human kindness that we rarely gave way to frustration or despair.

The first heavy rain drove down on us shortly after we had crossed the French border into Italy from Mentone. Vapour shrouded the villas and palms of the Riviera, and Hetty's tyres hissed, while the front wheel shot out sheets of spray like a destroyer in a choppy sea. The time came for our snack lunch, and we found shelter in a sprawling, shell-torn villa alongside the road. Through a curtain of water which gushed from the roof, we peered out of a doorway; beyond the palms, whose fronds sagged from the weight of moisture, stood a marble statue indifferent to the torrent which gushed around his pedestal.

Suddenly, from an adjoining room, glided a little old man. He scrutinised us for a moment in silence, but without hostility, and beckoned us to follow; with hardly a word he led us around terraces, through passages and great halls. Breakers crashing on the rocks outside sent jets of spray through gashes on the walls.

“War, bombs!”—he muttered sadly, surveying the desolation. He lit a fire for us in the kitchen hearth, and slipped silently away as we had our coffee and our tinned lunch.

"Do you suppose that he's the ghost of the former owner?” I asked, only half in jest. “Don't be macabre," replied Mollie, licking sardine off her fingers. Again we navigated onward over a road like a canal, swerving and pitching in the drenching, furious gusts. We were protected only by lightweight oilskins and Mollie's “boots” were improvised from lengths of inner tube tied up with string at the two ends.

At Genoa Voltri-a suburb of the sea-port--the water became deeper and muddier and the exhaust began to bubble. Only a few feet ahead a wild, brown torrent tumbled and roared over the approaches to a bridge. Now it is our habit to set off on our trips with limitless optimism, but mighty little cash, and in searching for accommodation we seek the advice of any friendly inhabitants. So we tacked about and set sail for a man on the steps of a nearby large building.

He had been watching our progress with sympathy, and when we asked him where we could pass this bleak evening, he promptly asked us inside. We found ourselves in the common-room of a fisher man's club. The tables were crowded with men in blue dungarees, who had been made inactive by the weather. Here we explained what we wanted as best we could in a language we improvised from French, Spanish and Catalan. “The only place near here is a de-luxe hotel a little way back” -they looked at our dripping oilskins and Mollie's red ‘boots’ -“but maybe that wouldn't suit you?”. We entirely agreed!

Part Two

Little matter. Hetty was bodily carried up the flight of steps into the clubroom, where she dripped all over the clubroom floor. We were shown into another room to change, and when we returned, crisp rolls, a plate of salami and a bottle of wine were laid for us on the table. Thus fortified, we were escorted outside, and men in waders carried us over the lake to the flat of a local tailor. Here we were shown a room with murals on the walls and numbers of highly active cherubs on a vaulted ceiling. Our hostess spoke broad Genoese, but was warmly welcoming.

However, we were not able to "turn in” then because at least a dozen of our hosts insisted that we should join them at a café, where we were served with sparkling red wine and delicious cream cakes. In clear, moving harmony they started to sing folk songs of the district, some swinging with a lilt, others plaintive and sad. When they had finished their repertoire, they turned to us for something English, but though we did our best, I was sorry for our victims! However, such was their courtesy that the applause would have flattered an opera star.

All the next morning the rain continued, and the floods swept past the bridge. Not until dawn the following day did we wave goodbye to our friends and start to squelch over the silt-covered cobbles, heading for Venice. Onward we whirred through the plains of Lombardy, where crops grow in perfect symmetry and where the careful peasants will not tolerate so much as one weed to rob the soil. It looked as if we should be delayed when we saw the great river Po in flood before us, with the causeway beyond the pontoon bridge partly swept away in the tide.

We advanced cautiously over the planks to investigate, and found men working at the far end. Three sturdy labourers put down their shovels and came forward to help us. With surprising strength they lifted Hetty and man-handled her through the water. But there were moments of suspense as the torrent tugged at our ankles, and Mollie looked on anxiously from the far bank until our precious steed was safely on the road again.

Venice is the only place which in all respects exceeded my expectations, and this despite a storm which broke soon after our arrival. Alongside one of the minor canals, near some gondolas now deserted by their oarsmen, we sheltered in a doorway. We were joined by a gentleman who, after listening to us talking, introduced himself in excellent English. He proved to be a Doctor of Philosophy, a professor, widely-travelled and most friendly. He guided us to a coffee bar and devoted the rest of the evening to showing us his city.

Finally, he invited us to his home for the night, and in the water-bus we churned under the bridges of the Grand Canal and out across the bay to the Lido. Although it was now after midnight, we must go to meet one of his friends—the Mayor of Venice! This gentleman answered our ringing in his dressing-gown, and in spite of the late hour he gave us a charming welcome.

PART THREE

Although we had a spell of sunshine the following morning from Venice to the frontier, at Gorizia the clouds gathered, and just as we entered the Yugoslav customs shed, the timbers creaked as the gale struck. The single naked bulb swung on its flex, and through the windows we contemplated Hetty as the hail bounced off her tank.

The officials, after perusing our touring documents, politely pointed out that our British papers had a statement clearly written in red ink-“Not valid for Yugoslavia" a little matter which I had failed to notice! Our visas were in order, but it looked as if our gremlin had played a trump card and won the game. However, my companion, who had endured the elements with amazing fortitude, was not going to be thwarted after so much discomfort. She achieved the near-impossible by literally arguing our way into the country, for after half an hour a friendly but harassed officer picked up the phone and, after speaking for a few moments, replaced the receiver with a smile. Came a moment's suspense—then, simply, “Proceed.”

The last rays of the sunset painted the snowy peaks of the Julian Alps ahead of us a vivid pink, and a distant range was periodically silhouetted by flashes from the storm rumbling in the distance. Soon we began winding through the hills, among dark pinewoods. The lamp spotted boughs and branches scattered over the highway, and ridges of gravel brought down by the deluge made the surface unstable. The solitude was impressive, and I felt like the helmsman at the tiller of a tiny boat far out to sea.

When we descended to the twinkling, spired city of Ljubliana, we could hear the clocks chiming midnight. We had expected to find a shabby town and a simple hotel, but the Hotel Sloan was a marble-fronted palace, and the band was still playing when we entered the reception hall. At breakfast we ate more butter than was good for our digestions. Later, during a thunder-hot morning, we headed for Zagreb, a hundred miles away. Within a dozen miles we were bumping over a cart-track, and it was evident that the main route had eluded us. For hours we floundered through the mire of farmyards, or whirled up clouds of grit from dusty tracks. Finally, in a valley, we rode through a saturated meadow, with our footrests creating a wake through the water, and regained the rolled gravel of the post-road.

Since leaving the frontier we had found the language problem a bit awkward, but Mollie kept producing dusty phrases of German like a conjuror producing unexpected rabbits; for this province had been under Austrian domination for a hundred years and German is still spoken as a secondary language by many of the peasants.

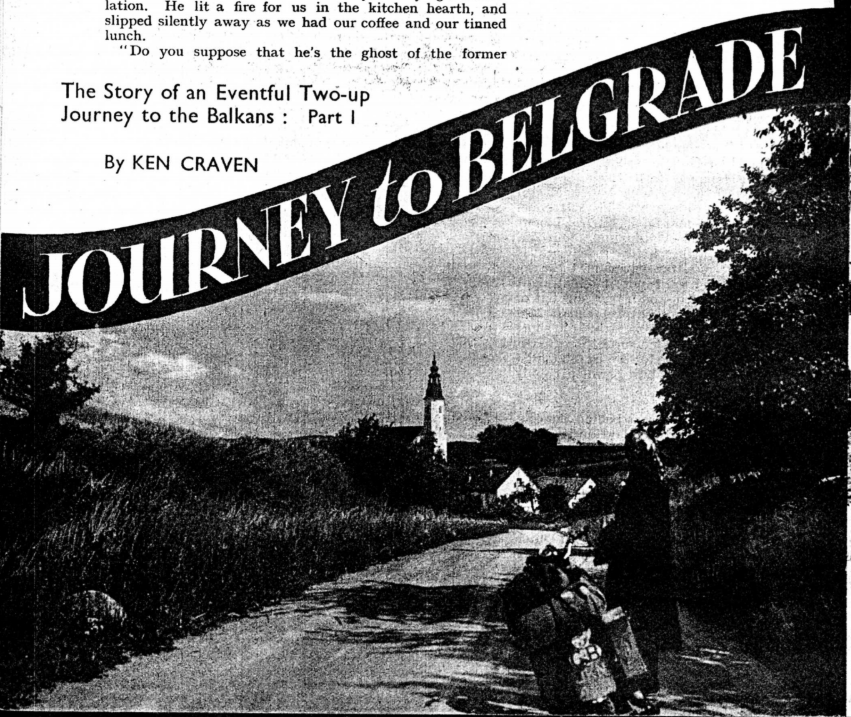

We ambled past communities of Swiss-looking chalets, all clustering around the quaint red pepper-pot steeples and their churches. Peasant girls in billowing skirts and embroidered aprons looked at us with friendly curiosity as we passed through their villages. Although the hills rose steeply, and wild torrents rushed through the valleys, it was a rich landscape, with lush meadows and grazing cattle, while the air was sweet with the perfumes of lime-trees, wild flowers and pines. We stopped in the sultry heat, picking and eating handfuls of wild strawberries on the alpine slopes.

At Zagreb, a city of wide avenues and modern buildings, we proceeded to Putnik—the Government travel agency and here we met Eva, who included English in her wide knowledge of languages. She led us to an hotel of deep carpets and gilded halls. At first, there was some problem over garaging the machine, but the cloakroom attendant was accustomed to checking-in most things—from officers' Sam Browne belts to live geese and leather gaiters. A motor cycle was a little unusual, but feasible, I was politely handed my check.

Eva spent the evening with us, and we visited the largest café I have ever seen, on several floors and with balconies and orchestras. Then we strolled out into the central square. A hundred or more singing youngsters arrived and, breaking formation, they cross-linked hands to form a circle which spun and wavered to the rhythm of their chanting. Then a couple leaped inside the ring, the tempo increased and the dancers bounced and spun and clicked their heels. Eva explained that they were University students.

“And why have they all come here to dance?” I asked.

“Because they feel like it !” was the logical enough retort.

The following morning, before we left Zagreb, Eva met us again to show us the picturesque market, where peasant women in wonderfully embroidered clothes presided over benches of hams, geese, butter, eggs, fat bacon, and bowls of cream. We began to feel dyspeptic at the sight of so much food!

In the main street we had another surprise, for we were shown a double-fronted shop window decorated attractively with British posters, and inside was a comfortable, large reading-room full of students and citizens, who had the choice of every newspaper published in Britain (or so it appeared to our dazed eyes, for we did not know the names of many of them ourselves). Shelves and tables held orderly piles of technical publications from Britain and all the weekly and monthly magazines imaginable - among them an old friend, The Motor Cycle, well-thumbed!

We left Zagreb regretfully, and paused on our way out to take photographs of the miniature railway built and operated by children, which carries peasants into the city for market days. These kiddies take turns in organizing and operating the services, and are enormously pleased with their own efficiency. There was a smooth stretch of cement road leaving the city, and we spun away the miles for a while. But our joy was soon shaken when we hurtled on to a surface of granite chips and shattering potholes, and a sign mocked us with, “Belgrade 489 km." From here on it was a case of picking our way in intermediary gears over the whole course.

They were hard and monotonous miles, but our journey was eased (if often delayed) by the most astounding hospitality. During the three days that we plodded on we spent not a single dinar - nor could we do so - except on petrol. Sitting on the wooden bench at a village restaurant we ate ham, red garlic sausage, onions, and rye bread, and washed down these “vittles" with strong wines. The other diners gathered around us, and in goodness knows what mixtures of languages we discussed our journey. There was some surprise when we offered to pay, for, apparently, it is the tradition that the friendly traveller is the guest of the countryside. .